Hello readers, I’m no longer posting new content on gafferongames.com

Please check out my new blog at mas-bandwidth.com!

Introduction

Hi, I’m Glenn Fiedler and welcome to Building a Game Network Protocol.

So far in this article series we’ve discussed how games read and write packets, how to unify packet read and write into a single function, how to fragment and re-assemble packets, and how to send large blocks of data over UDP.

Now in this article we’re going to bring everything together and build a client/server connection on top of UDP.

Background

Developers from a web background often wonder why games go to such effort to build a client/server connection on top of UDP, when for many applications, TCP is good enough. *

The reason is that games send time critical data.

Why don’t games use TCP for time critical data? The answer is that TCP delivers data reliably and in-order, and to do this on top of IP (which is unreliable, unordered) it holds more recent packets hostage in a queue while older packets are resent over the network.

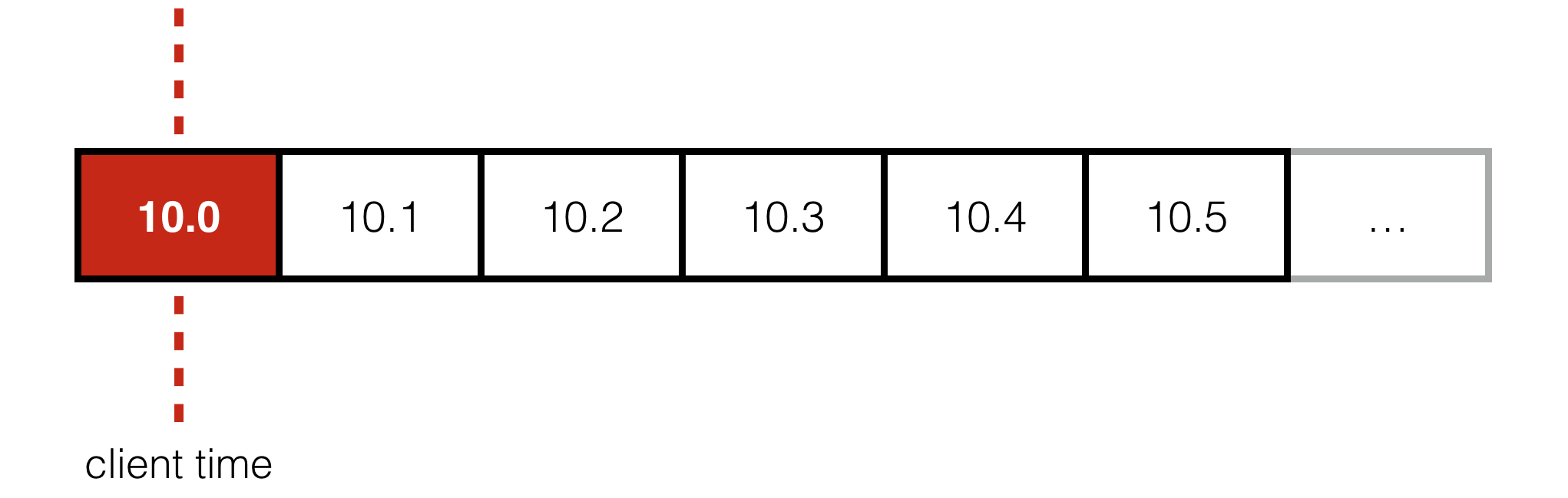

This is known as head of line blocking and it’s a huuuuuge problem for games. To understand why, consider a game server broadcasting the state of the world to clients 10 times per-second. Each client advances time forward and wants to display the most recent state it receives from the server.

But if the packet containing state for time t = 10.0 is lost, under TCP we must wait for it to be resent before we can access t = 10.1 and 10.2, even though those packets have already arrived and contain the state the client wants to display.

Worse still, by the time the resent packet arrives, it’s far too late for the client to actually do anything useful with it. The client has already advanced past 10.0 and wants to display something around 10.3 or 10.4!

So why resend dropped packets at all? BINGO! What we’d really like is an option to tell TCP: “Hey, I don’t care about old packets being resent, by they time they arrive I can’t use them anyway, so just let me skip over them and access the most recent data”.

Unfortunately, TCP simply does not give us this option :(

All data must be delivered reliably and in-order.

This creates terrible problems for time critical data where packet loss and latency exist. Situations like, you know, The Internet, where people play FPS games.

Large hitches corresponding to multiples of round trip time are added to the stream of data as TCP waits for dropped packets to be resent, which means additional buffering to smooth out these hitches, or long pauses where the game freezes and is non-responsive.

Neither option is acceptable for first person shooters, which is why virtually all first person shooters are networked using UDP. UDP doesn’t provide any reliability or ordering, so protocols built on top it can access the most recent data without waiting for lost packets to be resent, implementing whatever reliability they need in radically different ways to TCP.

But, using UDP comes at a cost:

UDP doesn’t provide any concept of connection.

We have to build that ourselves. This is a lot of work! So strap in, get ready, because we’re going to build it all up from scratch using the same basic techniques first person shooters use when creating their protocols over UDP. You can use this client/server protocol for games or non-gaming applications and, provided the data you send is time critical, I promise you, it’s well worth the effort.

* These days even web servers are transitioning to UDP via Google’s QUIC. If you still think TCP is good enough for time critical data in 2016, I encourage you to put that in your pipe and smoke it :)

Client/Server Abstraction

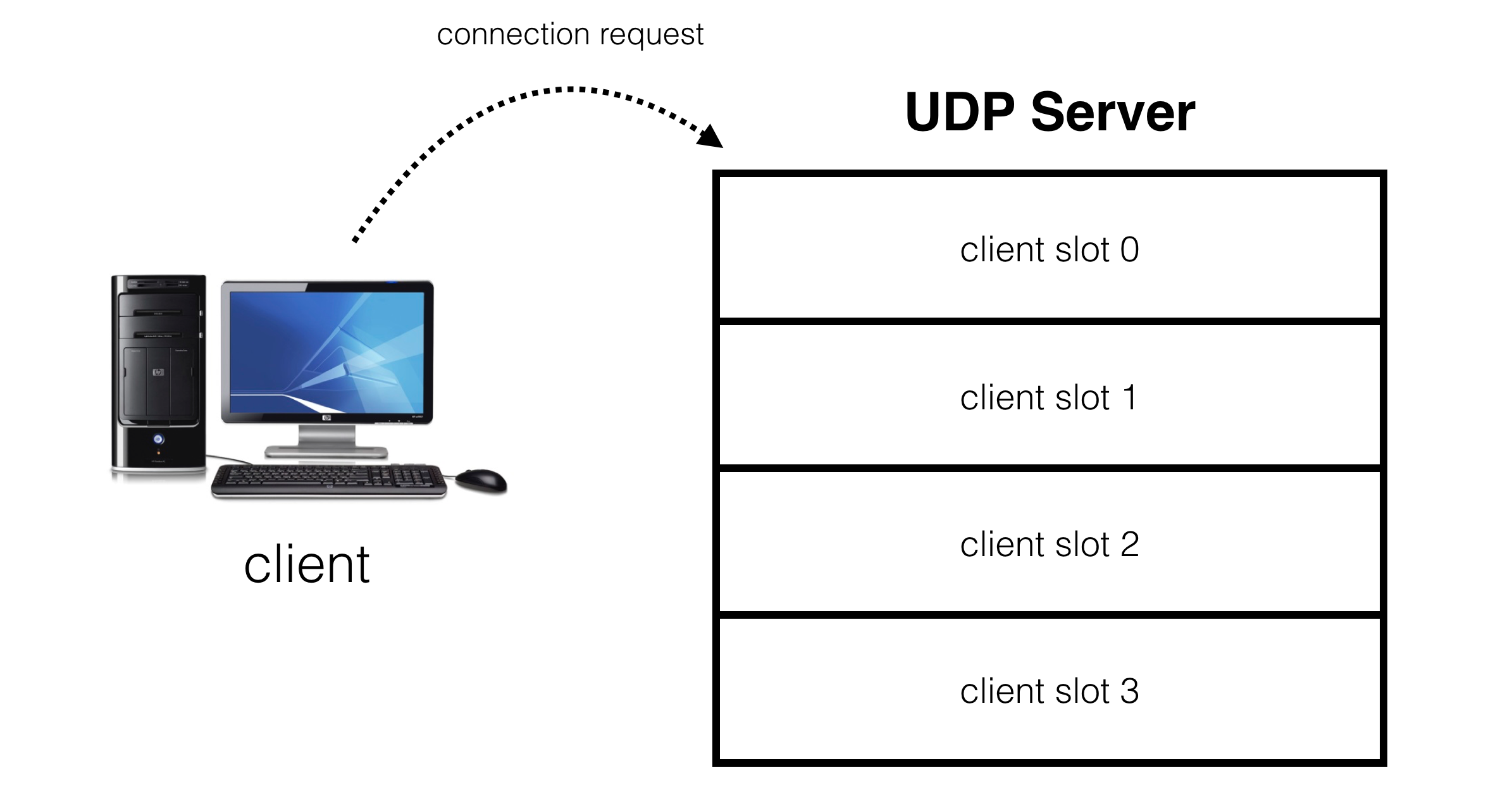

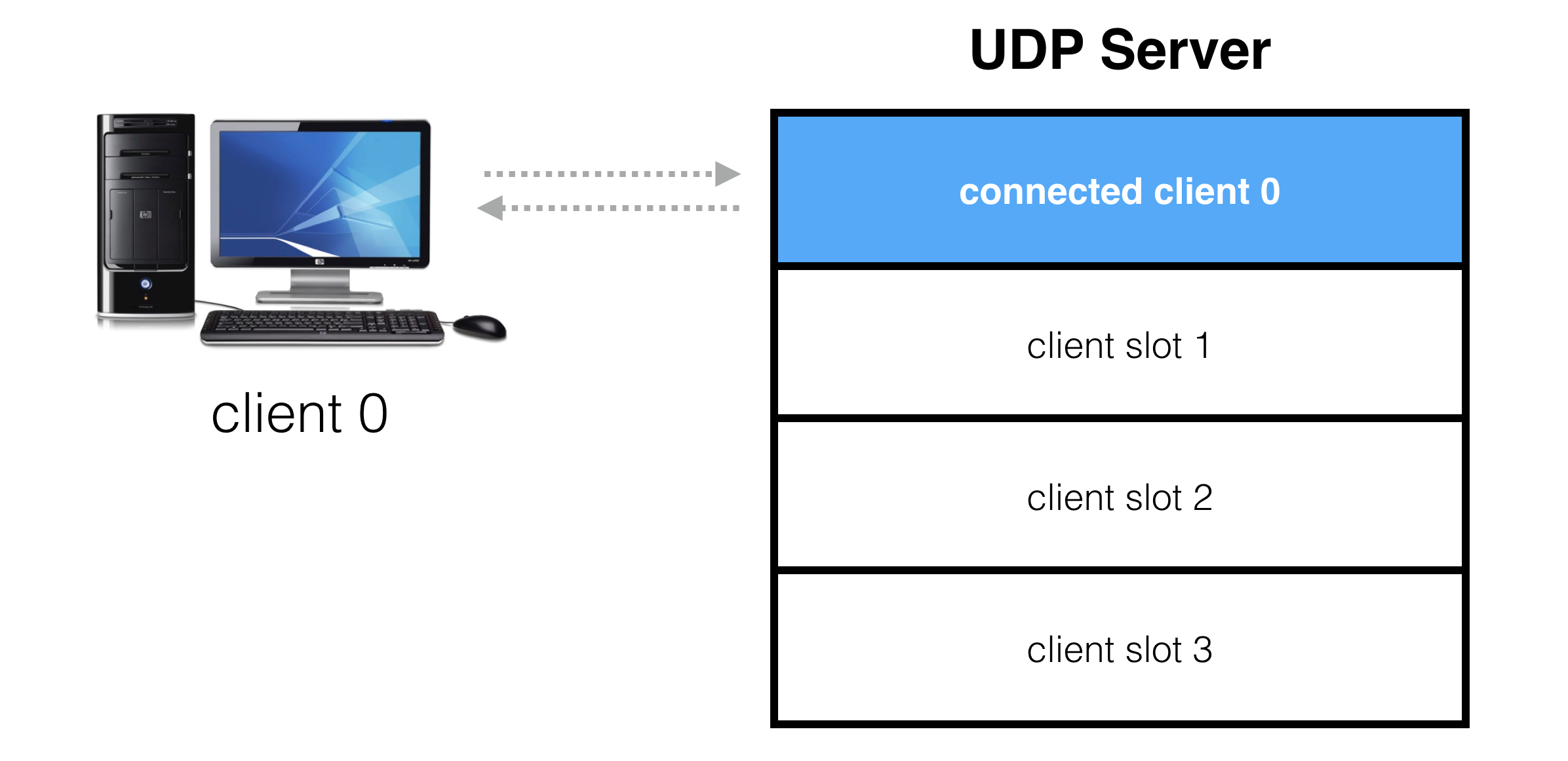

The goal is to create an abstraction on top of a UDP socket where our server presents a number of virtual slots for clients to connect to:

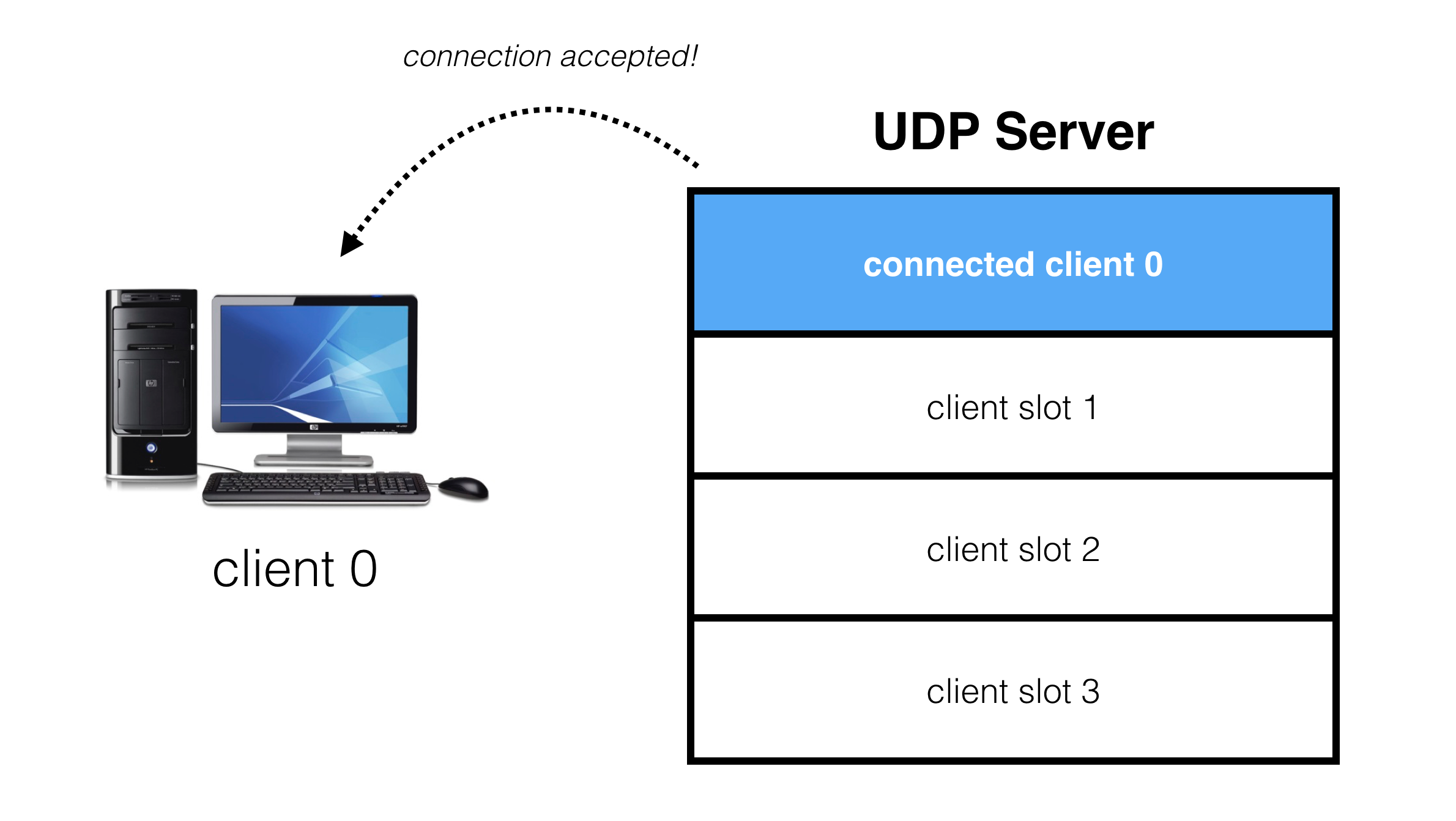

When a client requests a connection, it gets assigned to one of these slots:

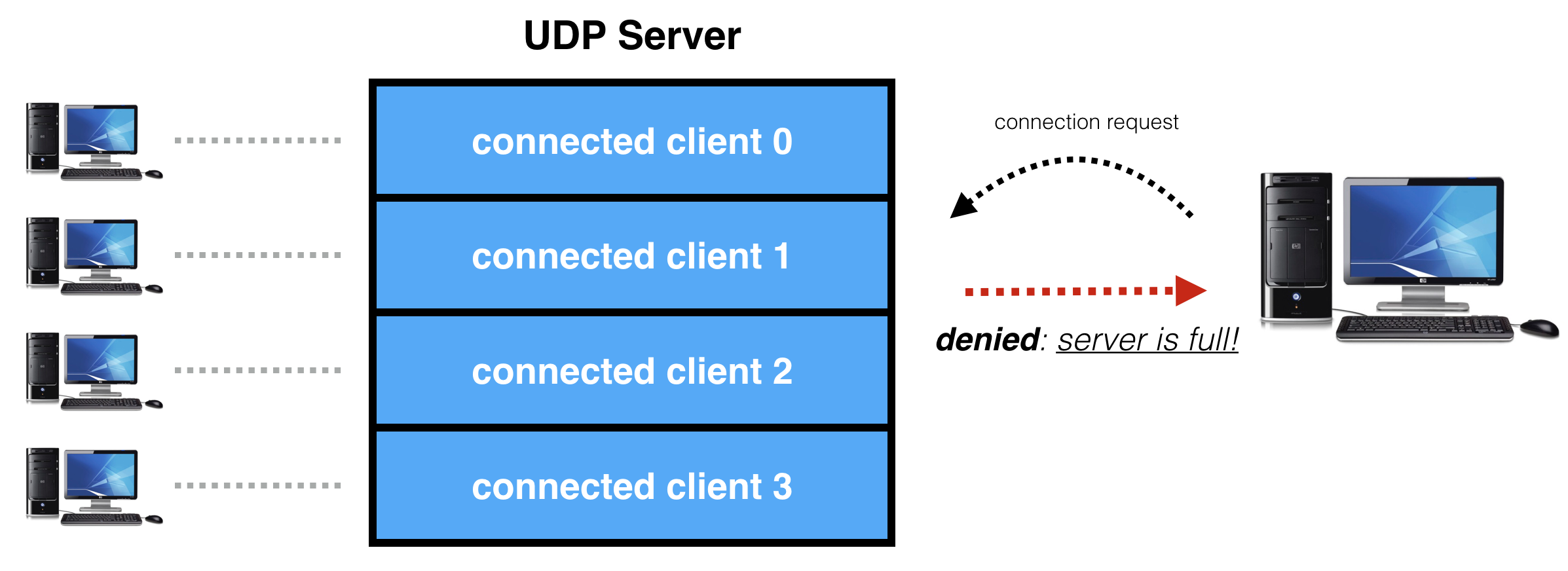

If a client requests connection, but no slots are available, the server is full and the connection request is denied:

Once a client is connected, packets are exchanged in both directions. These packets form the basis for the custom protocol between the client and server which is game specific.

In a first person shooter, packets are sent continuously in both directions. Clients send input to the server as quickly as possible, often 30 or 60 times per-second, and the server broadcasts the state of the world to clients 10, 20 or even 60 times per-second.

Because of this steady flow of packets in both directions there is no need for keep-alive packets. If at any point packets stop being received from the other side, the connection simply times out. No packets for 5 seconds is a good timeout value in my opinion, but you can be more aggressive if you want.

When a client slot times out on the server, it becomes available for other clients to connect. When the client times out, it transitions to an error state.

Simple Connection Protocol

Let’s get started with the implementation of a simple protocol. It’s a bit basic and more than a bit naive, but it’s a good starting point and we’ll build on it during the rest of this article, and the next few articles in this series.

First up we have the client state machine.

The client is in one of three states:

- Disconnected

- Connecting

- Connected

Initially the client starts in disconnected.

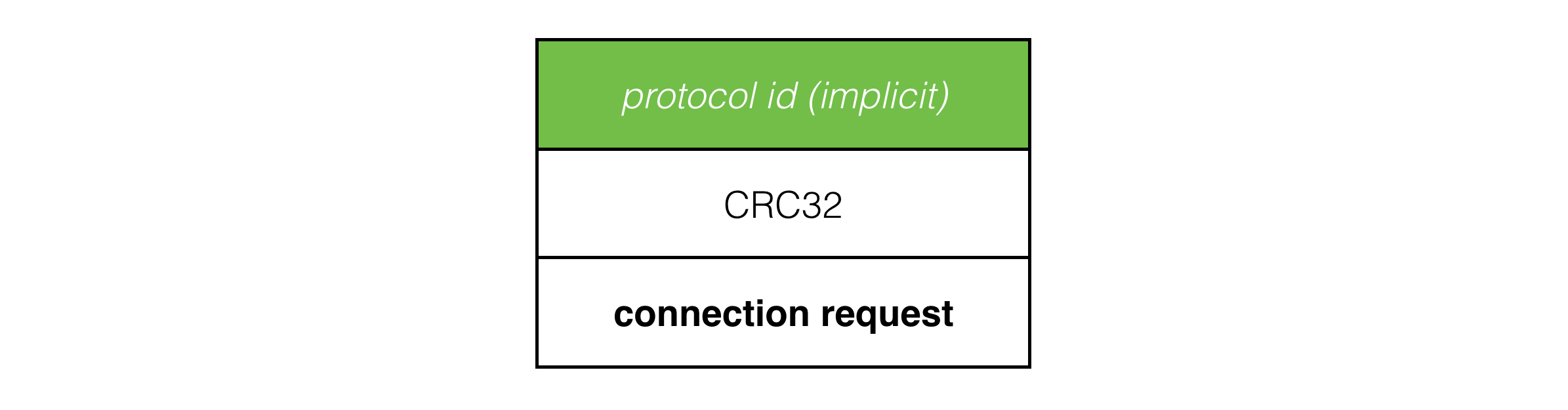

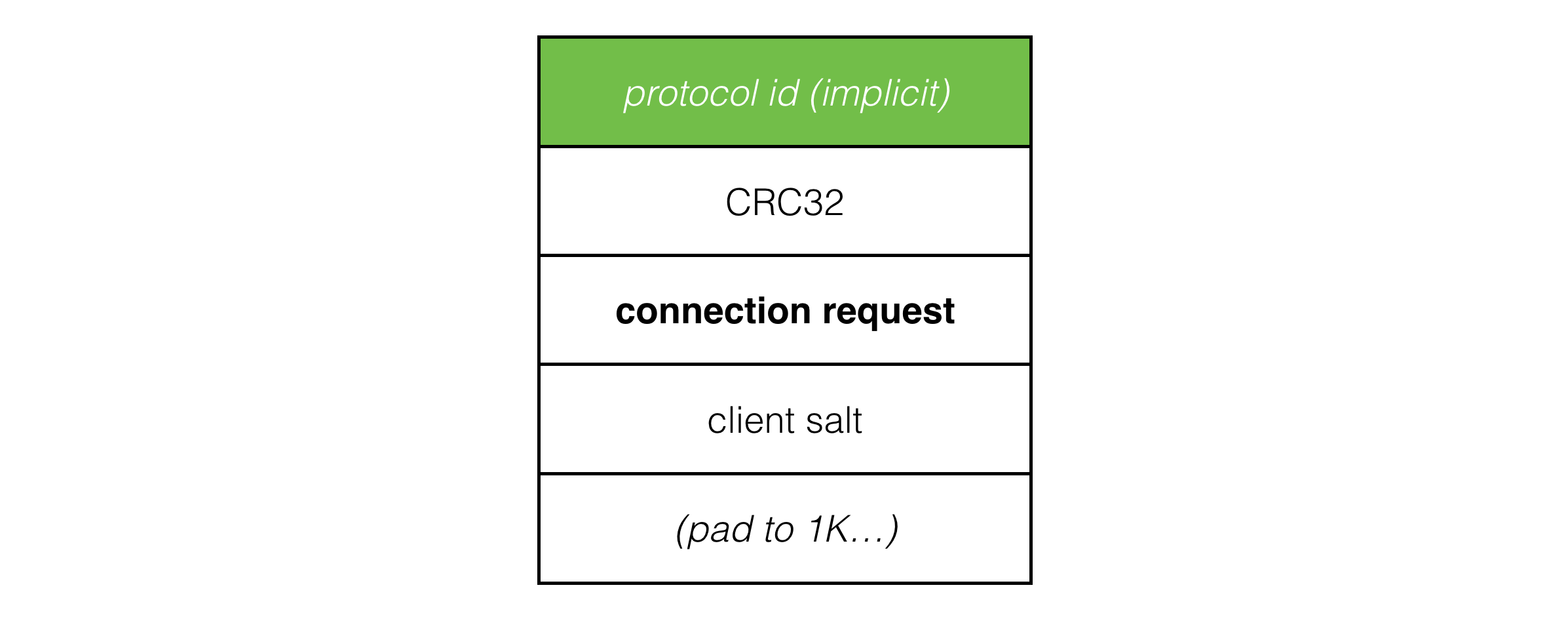

When a client connects to a server, it transitions to the connecting state and sends connection request packets to the server:

The CRC32 and implicit protocol id in the packet header allow the server to trivially reject UDP packets not belonging to this protocol or from a different version of it.

Since connection request packets are sent over UDP, they may be lost, received out of order or in duplicate.

Because of this we do two things: 1) we keep sending packets for the client state until we get a response from the server or the client times out, and 2) on both client and server we ignore any packets that don’t correspond to what we are expecting, since a lot of redundant packets are flying over the network.

On the server, we have the following data structure:

const int MaxClients = 64;

class Server

{

int m_maxClients;

int m_numConnectedClients;

bool m_clientConnected[MaxClients];

Address m_clientAddress[MaxClients];

};

Which lets the server lookup a free slot for a client to join (if any are free):

int Server::FindFreeClientIndex() const

{

for ( int i = 0; i < m_maxClients; ++i )

{

if ( !m_clientConnected[i] )

return i;

}

return -1;

}

Find the client index corresponding to an IP address and port:

int Server::FindExistingClientIndex( const Address & address ) const

{

for ( int i = 0; i < m_maxClients; ++i )

{

if ( m_clientConnected[i] && m_clientAddress[i] == address )

return i;

}

return -1;

}

Check if a client is connected to a given slot:

bool Server::IsClientConnected( int clientIndex ) const

{

return m_clientConnected[clientIndex];

}

… and retrieve a client’s IP address and port by client index:

const Address & Server::GetClientAddress( int clientIndex ) const

{

return m_clientAddress[clientIndex];

}

Using these queries we implement the following logic when the server processes a connection request packet:

-

If the server is full, reply with connection denied.

-

If the connection request is from a new client and we have a slot free, assign the client to a free slot and respond with connection accepted.

-

If the sender corresponds to the address of a client that is already connected, also reply with connection accepted. This is necessary because the first response packet may not have gotten through due to packet loss. If we don’t resend this response, the client gets stuck in the connecting state until it times out.

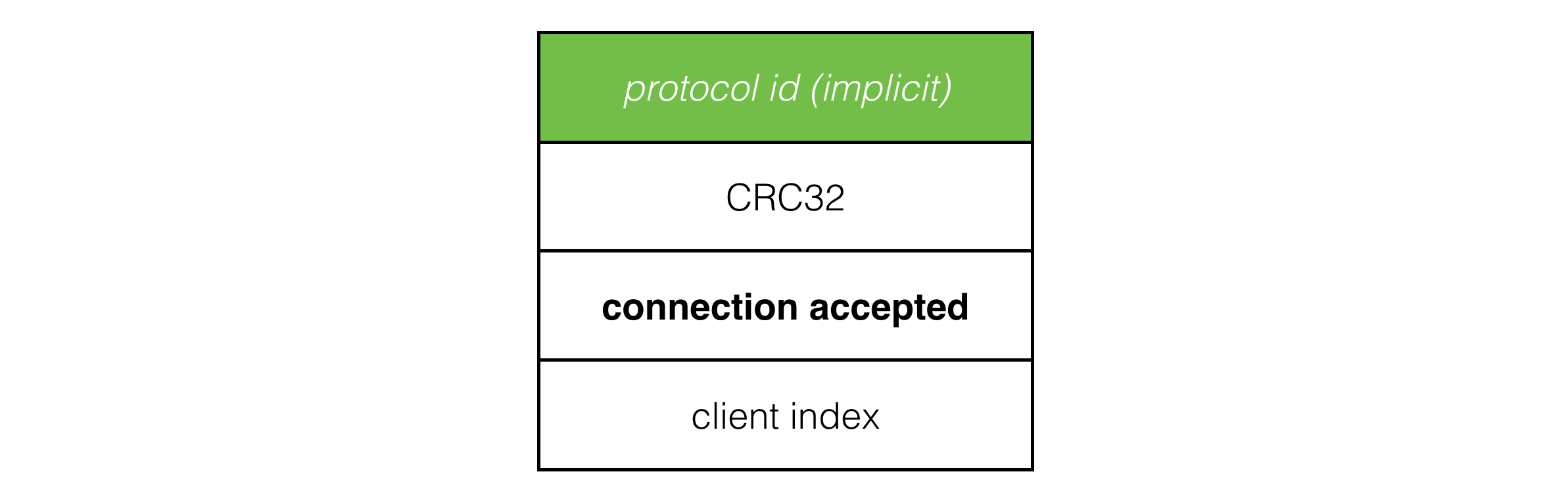

The connection accepted packet tells the client which client index it was assigned, which the client needs to know which player it is in the game:

Once the server sends a connection accepted packet, from its point of view it considers that client connected. As the server ticks forward, it watches connected client slots, and if no packets have been received from a client for 5 seconds, the slot times out and is reset, ready for another client to connect.

Back to the client. While the client is in the connecting state the client listens for connection denied and connection accepted packets from the server. Any other packets are ignored.

If the client receives connection accepted, it transitions to connected. If it receives connection denied, or after 5 seconds hasn’t received any response from the server, it transitions to disconnected.

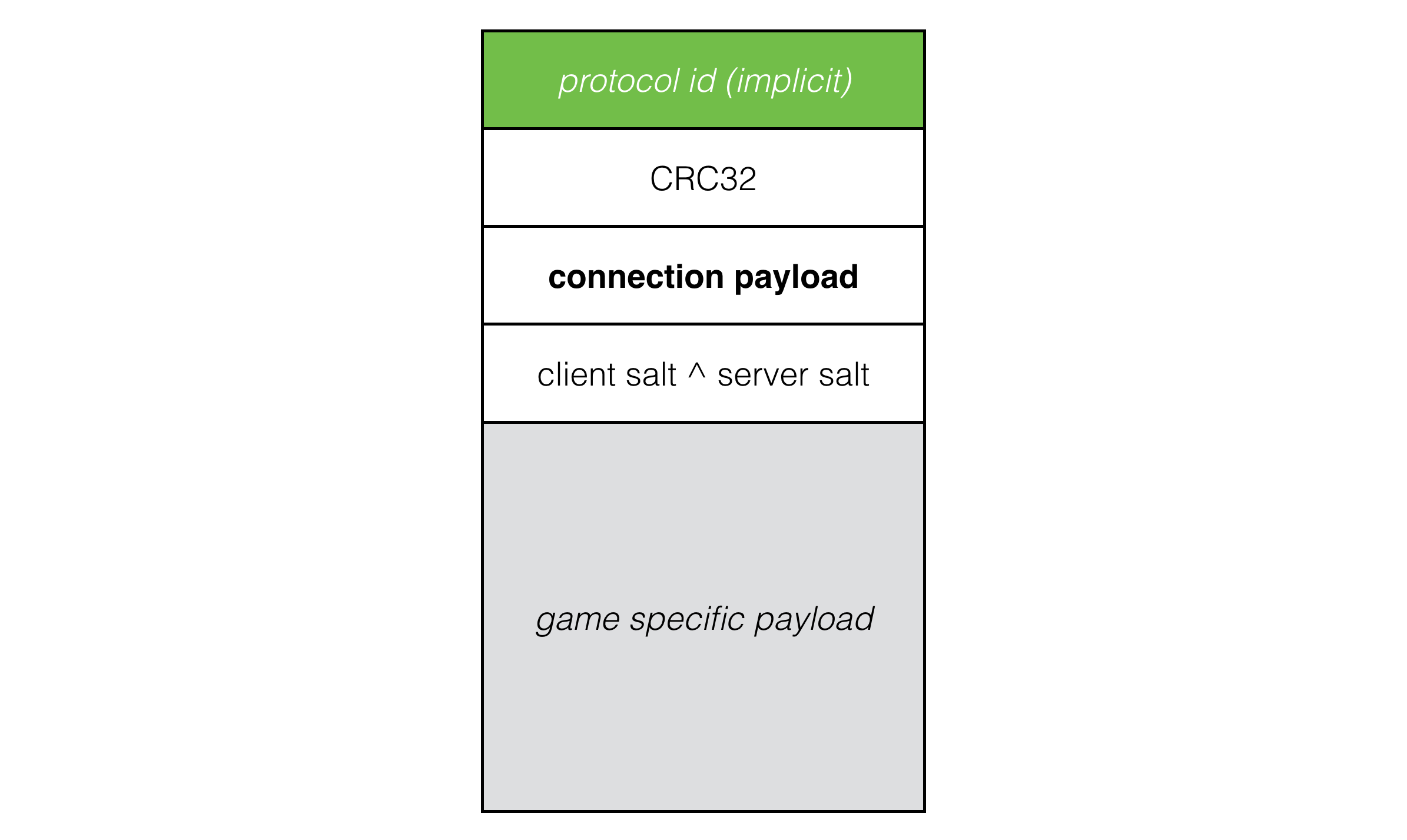

Once the client hits connected it starts sending connection payload packets to the server. If no packets are received from the server in 5 seconds, the client times out and transitions to disconnected.

Naive Protocol is Naive

While this protocol is easy to implement, we can’t use a protocol like this in production. It’s way too naive. It simply has too many weaknesses to be taken seriously:

-

Spoofed packet source addresses can be used to redirect connection accepted responses to a target (victim) address. If the connection accepted packet is larger than the connection request packet, attackers can use this protocol as part of a DDoS amplification attack.

-

Spoofed packet source addresses can be used to trivially fill all client slots on a server by sending connection request packets from n different IP addresses, where n is the number of clients allowed per-server. This is a real problem for dedicated servers. Obviously you want to make sure that only real clients are filling slots on servers you are paying for.

-

An attacker can trivially fill all slots on a server by varying the client UDP port number on each client connection. This is because clients are considered unique on an address + port basis. This isn’t easy to fix because due to NAT (network address translation), different players behind the same router collapse to the same IP address with only the port being different, so we can’t just consider clients to be unique at the IP address level sans port.

-

Traffic between the client and server can be read and modified in transit by a third party. While the CRC32 protects against packet corruption, an attacker would simply recalculate the CRC32 to match the modified packet.

-

If an attacker knows the client and server IP addresses and ports, they can impersonate the client or server. This gives an attacker the power to completely a hijack a client’s connection and perform actions on their behalf.

-

Once a client is connected to a server there is no way for them to disconnect cleanly, they can only time out. This creates a delay before the server realizes a client has disconnected, or before a client realizes the server has shut down. It would be nice if both the client and server could indicate a clean disconnect, so the other side doesn’t need to wait for timeout in the common case.

-

Clean disconnection is usually implemented with a disconnect packet, however because an attacker can impersonate the client and server with spoofed packets, doing so would give the attacker the ability to disconnect a client from the server whenever they like, provided they know the client and server IP addresses and the structure of the disconnect packet.

-

If a client disconnects dirty and attempts to reconnect before their slot times out on the server, the server still thinks that client is connected and replies with connection accepted to handle packet loss. The client processes this response and thinks it’s connected to the server, but it’s actually in an undefined state.

While some of these problems require authentication and encryption before they can be fully solved, we can make some small steps forward to improve the protocol before we get to that. These changes are instructive.

Improving The Connection Protocol

The first thing we want to do is only allow clients to connect if they can prove they are actually at the IP address and port they say they are.

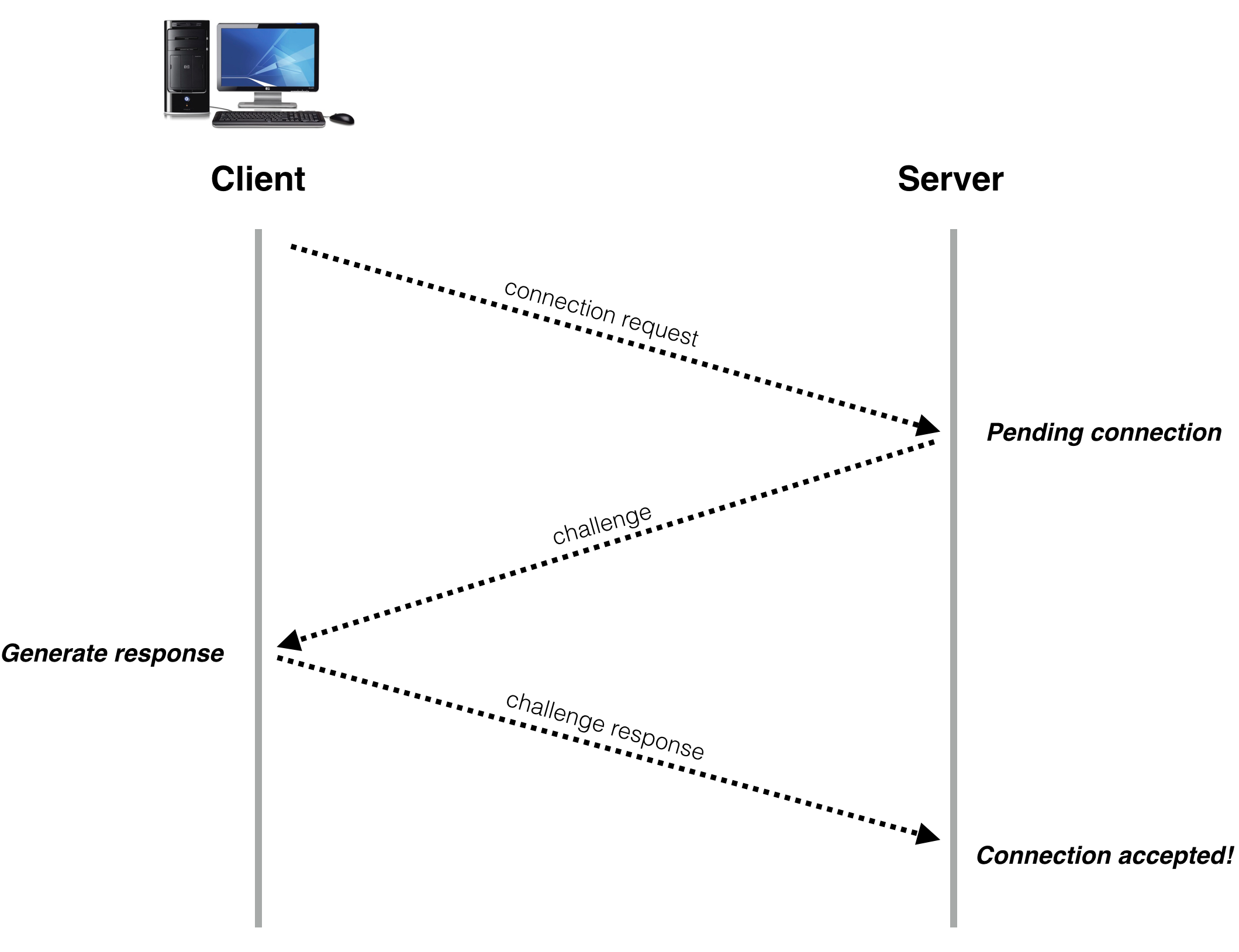

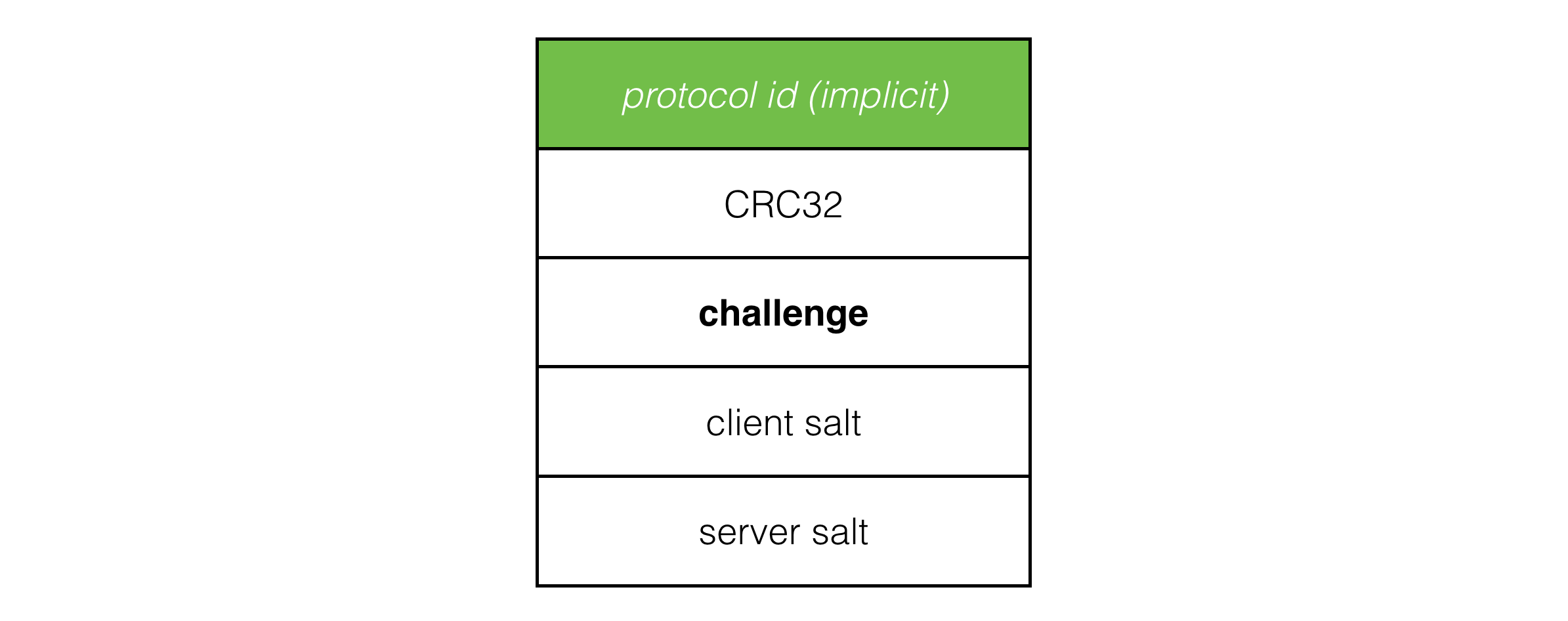

To do this, we no longer accept client connections immediately on connection request, instead we send back a challenge packet, and only complete connection when a client replies with information that can only be obtained by receiving the challenge packet.

The sequence of operations in a typical connect now looks like this:

To implement this we need an additional data structure on the server. Somewhere to store the challenge data for pending connections, so when a challenge response comes in from a client we can check against the corresponding entry in the data structure and make sure it’s a valid response to the challenge sent to that address.

While the pending connect data structure can be made larger than the maximum number of connected clients, it’s still ultimately finite and is therefore subject to attack. We’ll cover some defenses against this in the next article. But for the moment, be happy at least that attackers can’t progress to the connected state with spoofed packet source addresses.

Next, to guard against our protocol being used in a DDoS amplification attack, we’ll inflate client to server packets so they’re large relative to the response packet sent from the server. This means we add padding to both connection request and challenge response packets and enforce this padding on the server, ignoring any packets without it. Now our protocol effectively has DDoS minification for requests -> responses, making it highly unattractive for anyone thinking of launching this kind of attack.

Finally, we’ll do one last small thing to improve the robustness and security of the protocol. It’s not perfect, we need authentication and encryption for that, but it at least it ups the ante, requiring attackers to actually sniff traffic in order to impersonate the client or server. We’ll add some unique random identifiers, or ‘salts’, to make each client connection unique from previous ones coming from the same IP address and port.

The connection request packet now looks like this:

The client salt in the packet is a random 64 bit integer rolled each time the client starts a new connect. Connection requests are now uniquely identified by the IP address and port combined with this client salt value. This distinguishes packets from the current connection from any packets belonging to a previous connection, which makes connection and reconnection to the server much more robust.

Now when a connection request arrives and a pending connection entry can’t be found in the data structure (according to IP, port and client salt) the server rolls a server salt and stores it with the rest of the data for the pending connection before sending a challange packet back to the client. If a pending connection is found, the salt value stored in the data structure is used for the challenge. This way there is always a consistent pair of client and server salt values corresponding to each client session.

The client state machine has been expanded so connecting is replaced with two new states: sending connection request and sending challenge response, but it’s the same idea as before. Client states repeatedly send the packet corresponding to that state to the server while listening for the response that moves it forward to the next state, or back to an error state. If no response is received, the client times out and transitions to disconnected.

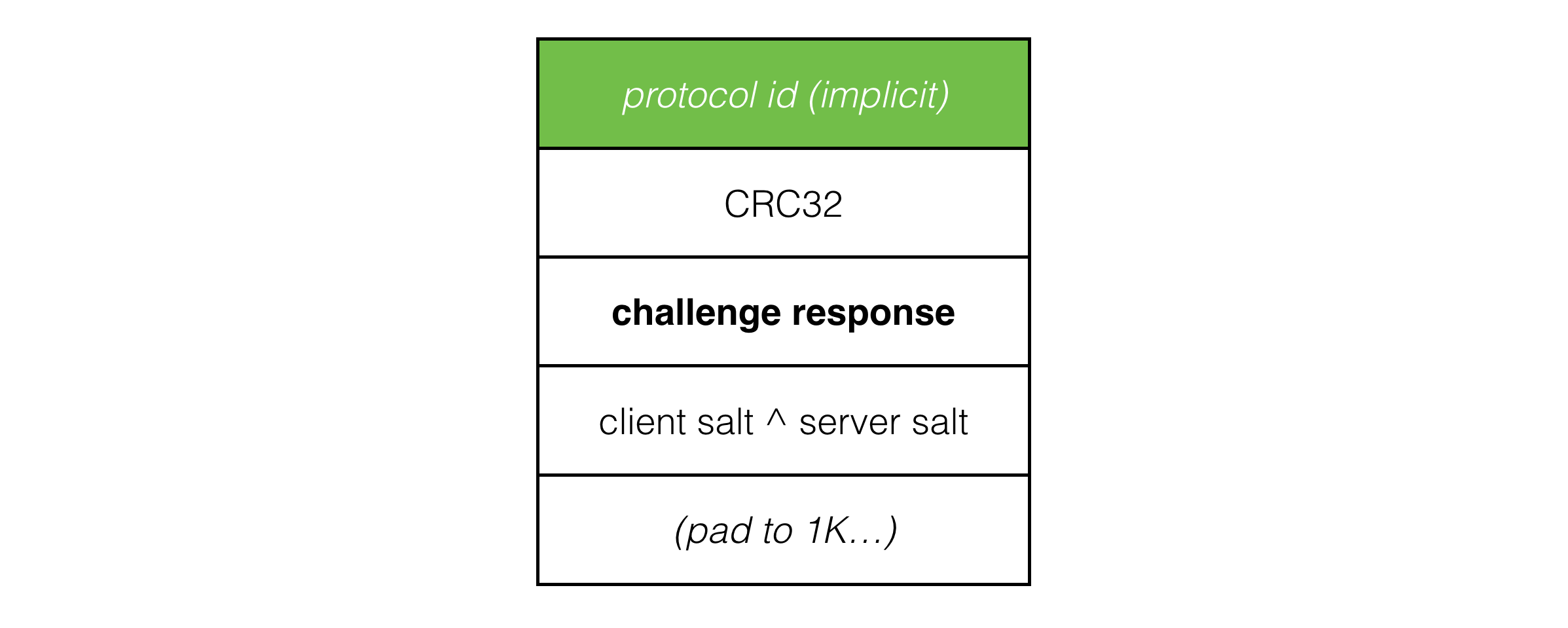

The challenge response sent from the client to the server looks like this:

The utility of this being that once the client and server have established connection, we prefix all payload packets with the xor of the client and server salt values and discard any packets with the incorrect salt values. This neatly filters out packets from previous sessions and requires an attacker to sniff packets in order to impersonate a client or server.

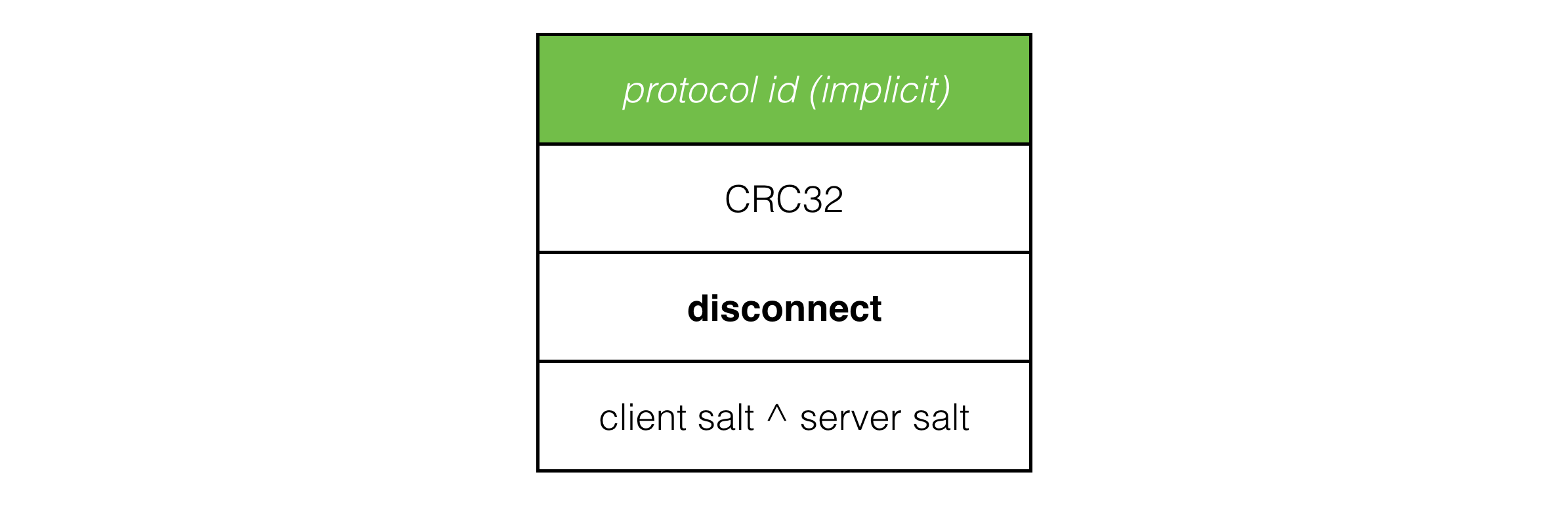

Now that we have at least a basic level of security, it’s not much, but at least it’s something, we can implement a disconnect packet:

And when the client or server want to disconnect clean, they simply fire 10 of these over the network to the other side, in the hope that some of them get through, and the other side disconnects cleanly instead of waiting for timeout.

Conclusion

We now have a much more robust protocol. It’s secure against spoofed IP packet headers. It’s no longer able to be used as port of DDoS amplification attacks, and with a trivial xor based authentication, we are protected against casual attackers while client reconnects are much more robust.

But it’s still vulnerable to a sophisticated actors who can sniff packets:

-

This attacker can read and modify packets in flight.

-

This breaks the trivial identification based around salt values…

-

… giving an attacker the power to disconnect any client at will.

To solve this, we need to get serious with cryptography to encrypt and sign packets so they can’t be read or modified by a third party.

NEXT ARTICLE: Securing Dedicated Servers.

Hello readers, I’m no longer posting new content on gafferongames.com