Hello readers, I’m no longer posting new content on gafferongames.com

Please check out my new blog at mas-bandwidth.com!

Introduction

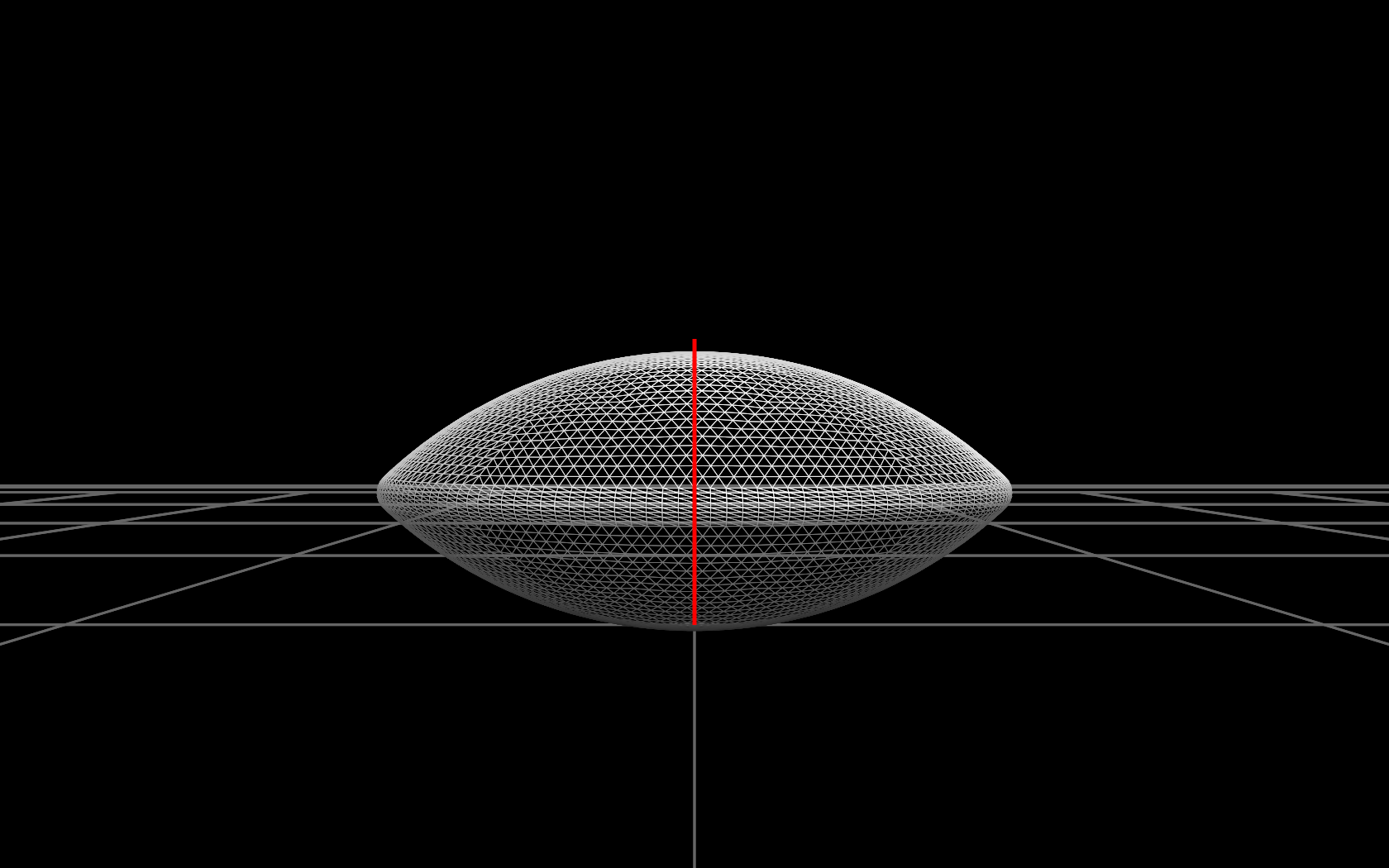

Hi, I’m Glenn Fiedler. Welcome to Virtual Go, my project to create a physically accurate computer simulation of a Go board and stones.

So far in this series, we have mathematically defined the go stone, rendered it, determined how it moves and rotates, and discussed how its shape affects how it responds to collisions.

Now in this article we reach our first milestone:

A go stone bouncing and coming to rest on the go board.

We’re going do this using a technique called impulse-based collision response.

The concept is simple. To handle a collision we apply an impulse, an instantaneous change in momentum, at the point of impact to make the go stone bounce.

Linear Collision Response

We now pick up where we left off at the end of the collision detection article.

We have a contact point and a contact normal for the collision.

Let’s start by calculating a collision response impulse without rotation.

First, take the dot product of the linear momentum of the go stone with the contact normal. If this value is less than zero, it means the go stone is moving towards the go board, and we need to apply an impulse.

To calculate the impulse we need the concept of ’elasticity’. If the collision is perfectly elastic, the go stone bounces off the board without losing any energy:

If the collision is inelastic then the go stone loses all its vertical motion post-collision and slides along the surface of the board:

What we really want is something in between:

To support this we introduce a new concept called the ‘coefficient of restitution’. When this value is 1 the collision is perfectly elastic, when it is 0 the collision is inelastic. At 0.5, it’s halfway between.

This gives the following formula:

[latex]j = -( 1 + e ) \boldsymbol{p} \cdot \boldsymbol{n}[/latex]

Where:

- j is the magnitude of the collision impulse

- e is the coefficient of restitution [0,1]

- p is the linear momentum of the go stone

- n in the contact normal for the collision

Note that the direction of the collision impulse is always along the contact normal, so to apply the impulse just multiply the contact normal by j and add it to the linear momentum vector.

Here’s the code that does this:

void ApplyLinearCollisionImpulse( StaticContact & contact, float e )

{

float mass = contact.rigidBody->mass;

float d = dot( contact.rigidBody->linearMomentum, contact.normal );

float j = max( - ( 1 + e ) * d, 0 );

contact.rigidBody->linearMomentum += j * contact.normal;

}

And here’s the result:

Now the stone is definitely bouncing, but in the real world stones don’t usually hit the board perfectly flat like this. In the common case, they hit at an angle and the collision makes the stone rotate.

Collision Response With Rotation

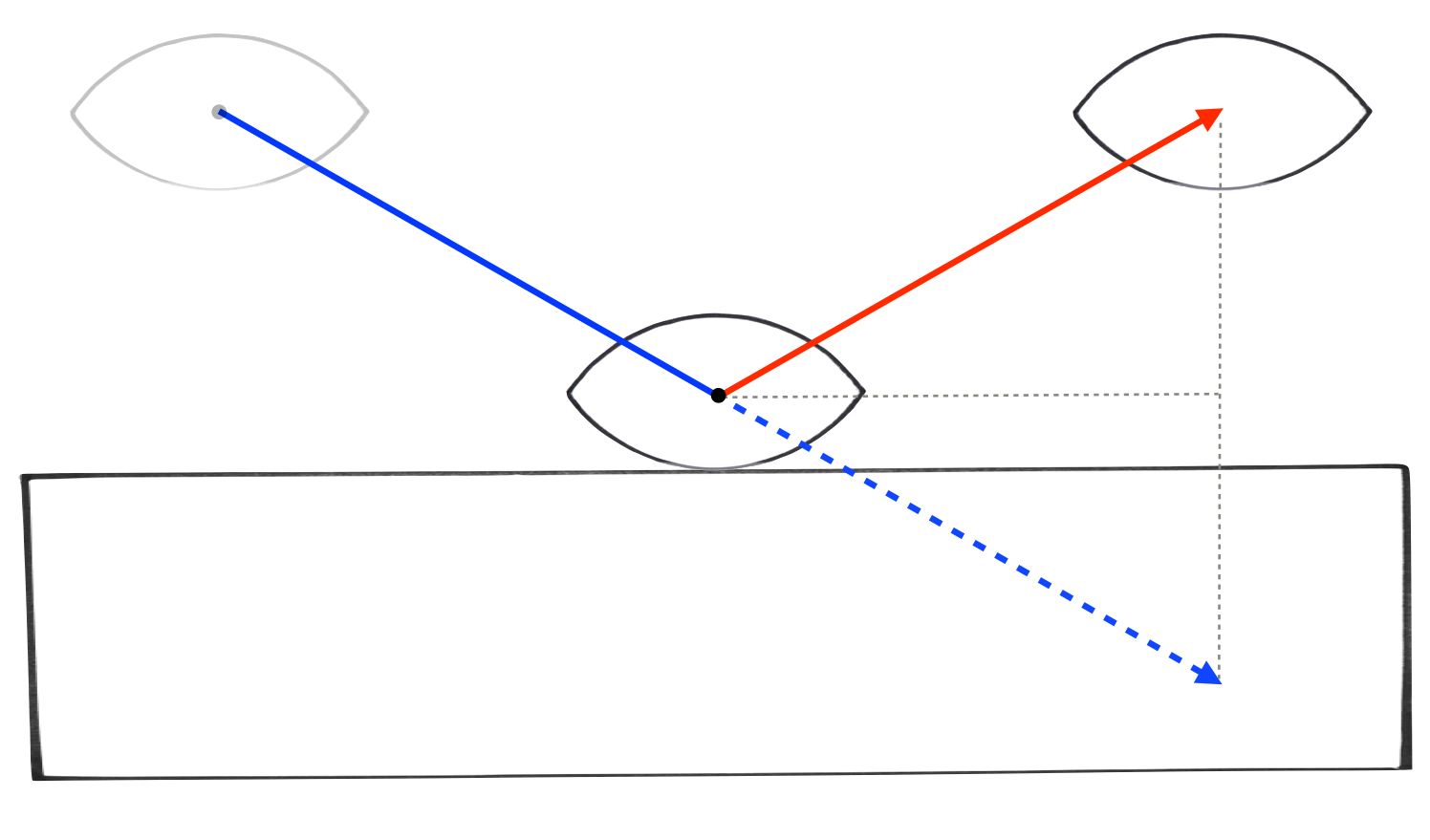

To capture this effect we need to calculate collision response with rotation.

Above you can see the effect that we want. If a stone were to collide with the board like this, we know from experience that it would rotate in response.

We start by calculating the velocity of the stone at the contact point, and take the dot product of this vs. the contact normal to check if the stone is moving towards the board. This is necessary because when the stone is rotating, different points on the stone have different velocities.

Next, we apply a collision impulse along the contact normal with magnitude j except this impulse is applied at the contact point instead of the center of mass of the stone. This gives the collision response its rotational effect.

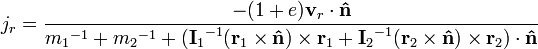

Here is the general equation for the magnitude of this collision impulse.

You can find a derivation of this result on wikipedia.

Understandably this is quite complex, but in our case the go board never moves, so we can simplify the equation by assigning zero velocity and infinite mass to the second body. This leads to the following, simpler equation:

todo: need a solution to convert across all the latex equations…

[latex]j = \dfrac{ -( 1 + e ) \boldsymbol{v} \cdot \boldsymbol{n} } { m^{-1} + ( \boldsymbol{I^{-1}} ( \boldsymbol{r} \times \boldsymbol{n} ) \times \boldsymbol{r} ) \cdot \boldsymbol{n} }[/latex]

Where:

- j is the magnitude of the collision impulse

- e is the coefficient of restitution [0,1]

- n in the contact normal for the collision

- v is the the go stone velocity at the contact point

- r is the contact point minus the center of the go stone

- I is the inertia tensor of the go stone

- m is the mass of the go stone

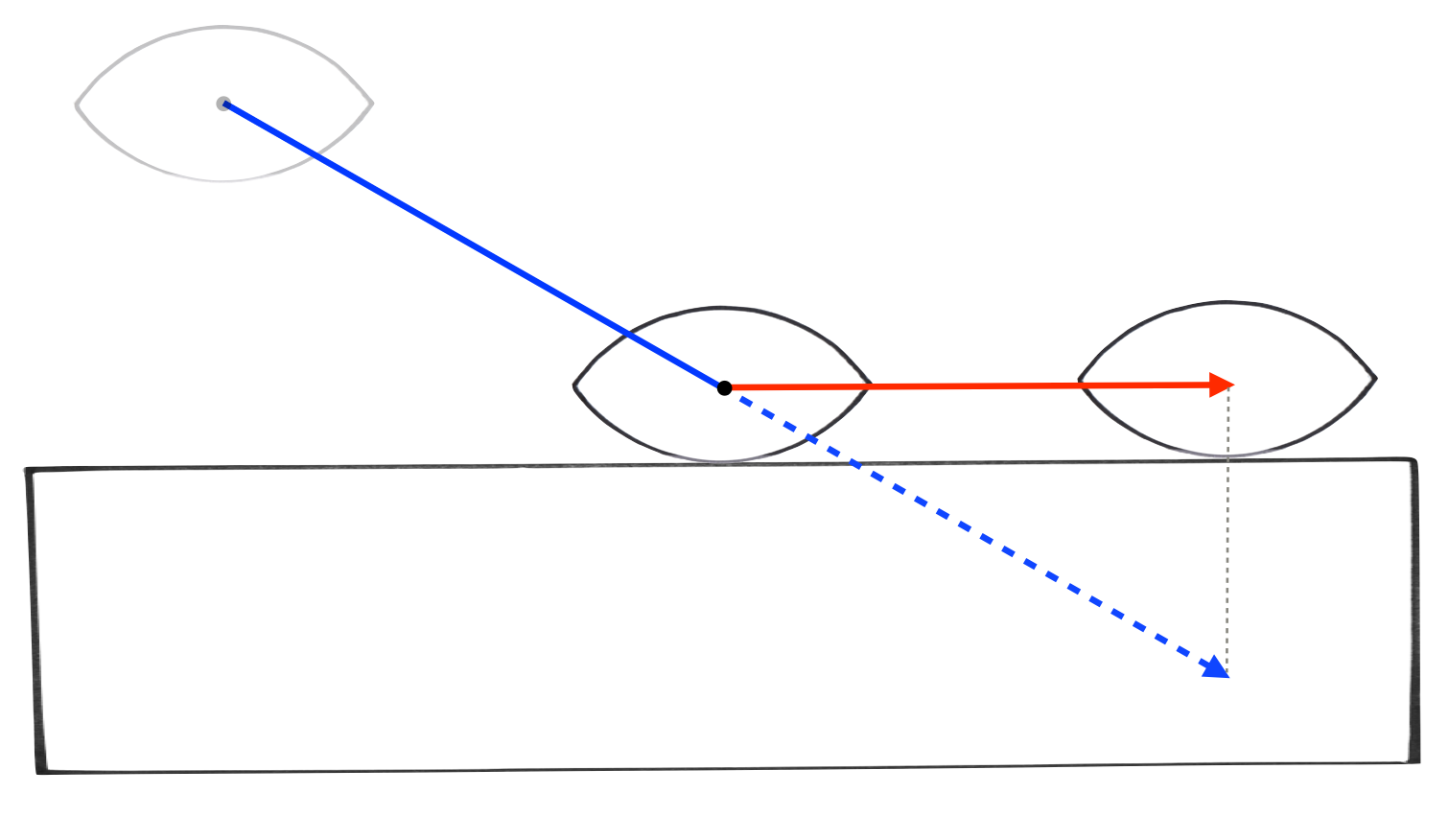

Here is the result of our collision response with rotational effects:

As you can see, collision response working properly and induces rotation when the go stone hits the board at an angle. It is also able to handle the stone hitting the board while rotating.

Coulomb Friction

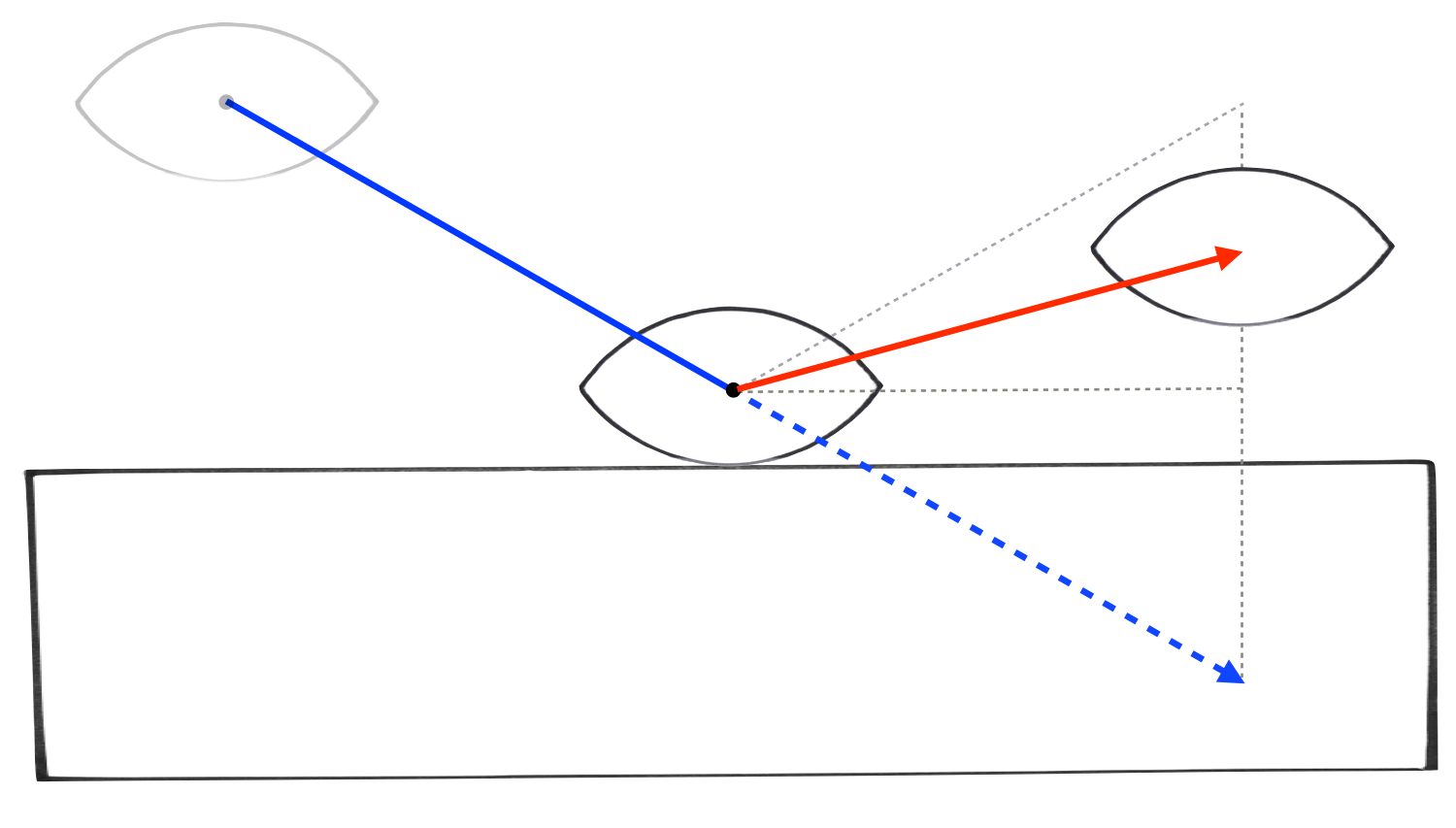

We don’t often get to see friction-less collisions in the real world so the video above looks a bit strange. To get realistic behavior out of the go stone, we need to add friction.

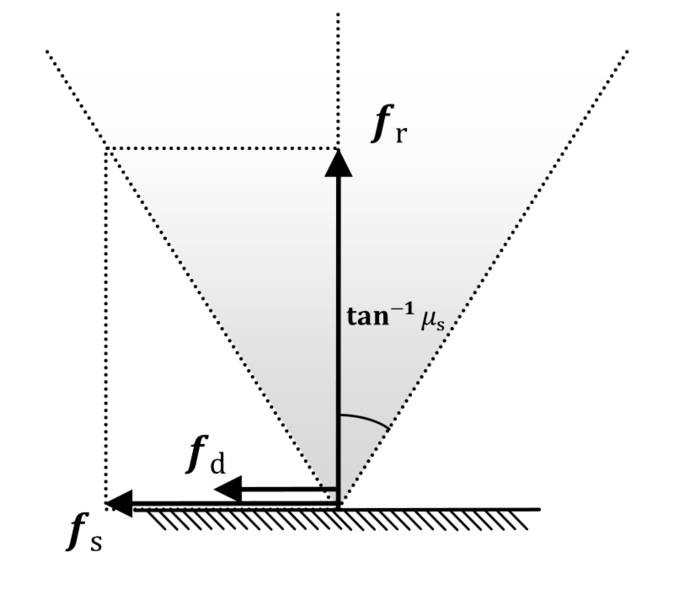

We’ll model sliding friction using the Coulomb friction model.

In this model, the friction impulse is proportional the magnitude of the normal impulse j and is limited by a friction cone defined by the coefficient of friction u:

Lower friction coefficient values mean less friction, higher values mean more friction. Typical values for the coefficient of friction are in the range [0,1].

Calculation of the Coulomb friction impulse is performed much like the calculation of the normal impulse except this time the impulse is in the tangent direction against the direction of sliding.

Here is the formula for calculating the magnitude of the friction impulse:

[latex]j_t = \dfrac{ - \boldsymbol{v} \cdot \boldsymbol{t} } { m^{-1} + ( \boldsymbol{I^{-1}} ( \boldsymbol{r} \times \boldsymbol{t} ) \times \boldsymbol{r} ) \cdot \boldsymbol{t} }[/latex]

Where:

- jt is the magnitude of the friction impulse (pre-cone limit)

- u is the coefficient of friction [0,1]

- t in the tangent vector in the direction of sliding

- v is the the go stone velocity at the contact point

- r is the contact point minus the center of the go stone

- I is the inertia tensor of the go stone

- m is the mass of the go stone

Which gives the following result:

Which looks much more realistic!

Rolling Friction

Due to its shape (and the inertia tensor from the previous article), the go stone really prefers to rotate about axes on the xz plane instead of around the y axis.

I was able to reproduct this effect in the simulation. Adding a torque that spins go stone around the y axis made it stand up and spin like a coin:

This is pretty cool and is totally emergent from the shape of the go stone. The only problem is that it spins like this forever.

Why is it spinning for so long? Shouldn’t coulomb friction handle this for us?

No. Coulomb friction only handles friction when the two surfaces are sliding relative to each other. Here at the point of contact, the stone is spinning about that point, not sliding, so from coulomb friction point of view, the contact point is stationary and no friction is applied.

It turns out that sliding friction is just one type of friction and there are many others. What we have in this case is a combination of rolling and spinning friction.

I had very little patience at this point so I came up with my own hack approximation of spinning and rolling friction that gives me the result that I want: vibrant motion at high energies but slightly damped so the stone slows down, collapses from spinning, wobbles a bit and then come to rest.

My hack was to apply exponential decay (eg. linearVelocity *= factor [0.9990-0.9999] each frame) to linear and angular velocity. The decay factor was linear interpolated between two key speeds such that there was more damping at low speeds and much less at high speeds. There is no physical basis for this, it’s just a hack to get the behavior I want.

With a bit of tuning, it seems to work reasonably well:

Hello readers, I’m no longer posting new content on gafferongames.com